this text, I’ll present you the right way to use two well-liked Python libraries to hold out some geospatial evaluation of site visitors accident knowledge throughout the UK.

I used to be a comparatively early adopter of DuckDB, the quick OLAP database, after it turned out there, however solely just lately realised that, via an extension, it provided a lot of doubtlessly helpful geospatial features.

Geopandas was new to me. It’s a Python library that makes working with geographic knowledge really feel like working with common pandas, however with geometry (factors, traces, polygons) in-built. You possibly can learn/write commonplace GIS codecs (GeoJSON, Shapefile, GeoPackage), manipulate attributes and geometries collectively, and shortly visualise layers with Matplotlib.

Desperate to check out the capabilities of each, I set about researching a helpful mini-project that will be each attention-grabbing and a useful studying expertise.

Lengthy story quick, I made a decision to strive utilizing each libraries to find out the most secure metropolis within the UK for driving or strolling round. It’s potential that you possibly can do every thing I’m about to indicate utilizing Geopandas by itself, however sadly, I’m not as accustomed to it as I’m with DuckDB, which is why I used each.

A number of floor guidelines.

The accident and casualty knowledge I’ll be utilizing is from an official UK authorities supply that covers the entire nation. Nonetheless, I’ll be specializing in the information for less than six of the UK’s largest cities: London, Edinburgh, Cardiff, Glasgow, Birmingham, and Manchester.

My technique for figuring out the “most secure” metropolis might be to calculate the overall variety of street traffic-related casualties in every metropolis over a five-year interval and divide this quantity by the realm of every metropolis in km². This might be my “security index”, and the decrease that quantity is, the safer town.

Getting our metropolis boundary knowledge

This was arguably essentially the most difficult a part of the complete course of.

Reasonably than treating a “metropolis” as a single administrative polygon, which ends up in varied anomalies when it comes to metropolis areas, I modelled every one by its built-up space (BUA) footprint. I did this utilizing the Workplace of Nationwide Statistics (ONS) Constructed-Up Areas map knowledge layer after which aggregated all BUA elements that fall inside a wise administrative boundary for that location. The masks comes from the official ONS boundaries and is chosen to replicate every wider city space:

- London → the London Area (Areas Dec 2023).

- Manchester → the union of the ten Larger Manchester Native Authority Districts (LAD ) for Could 2024.

- Birmingham → the union of the 7 West Midlands Mixed Authority LADs.

- Glasgow → the union of the 8 Glasgow Metropolis Area councils.

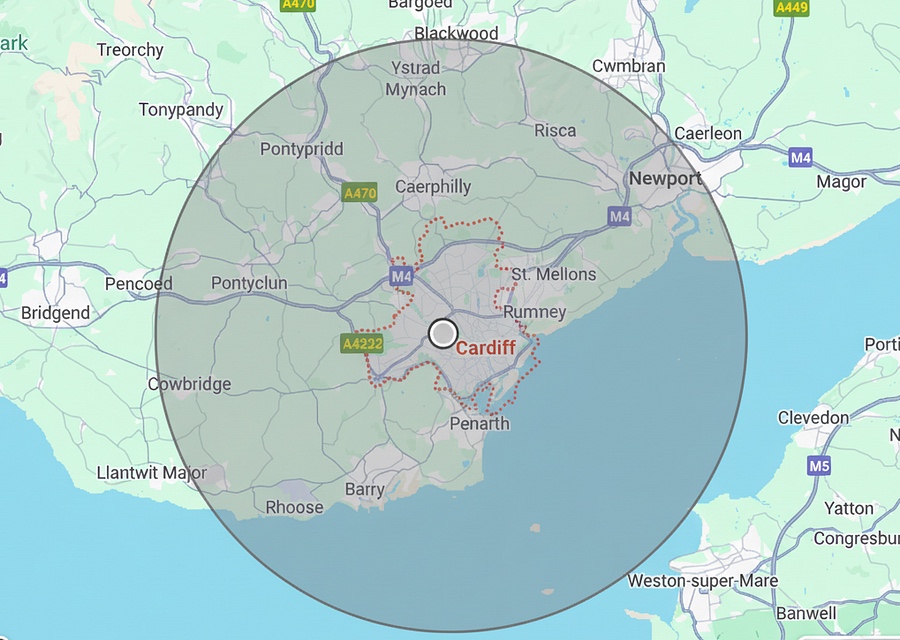

- Edinburgh and Cardiff → their single LAD.

How the polygons are in-built code

I downloaded boundary knowledge straight from the UK Workplace for Nationwide Statistics (ONS) ArcGIS FeatureServer in GeoJSON format utilizing the requests library. For every metropolis we first construct a masks from official ONS admin layers: the London Area (Dec 2023) for London; the union of Native Authority Districts (LAD, Could 2024) for Larger Manchester (10 LADs), the West Midlands core (7 LADs) and the Glasgow Metropolis Area (8 councils); and the single LAD for Edinburgh and Cardiff.

Subsequent, I question the ONS Constructed-Up Areas (BUA 2022) layer for polygons intersecting the masks’s bounding field, holding solely these that intersect the masks, and dissolve (merge) the outcomes to create a single multipart polygon per metropolis (“BUA 2022 mixture”). Knowledge are saved and plotted in EPSG:4326 (WGS84), i.e latitude and longitude are expressed as levels. When reporting areas, we reproject them to EPSG:27700 (OSGB) and calculate the realm in sq. kilometres to keep away from distortions.

Every metropolis boundary knowledge is downloaded to a GeoJSON file and loaded into Python utilizing the geopandas and requests libraries.

To indicate that the boundary knowledge we have now is appropriate, the person metropolis layers are then mixed right into a single Geodataframe, reprojected right into a constant coordinate reference system (EPSG:4326), and plotted on prime of a clear UK define derived from the Pure Earth dataset (through a GitHub mirror). To focus solely on the mainland, we crop the UK define to the bounding field of the cities, excluding distant abroad territories. The world of every metropolis can also be calculated.

Boundary knowledge licensing

All of the boundary datasets I’ve used are open knowledge with permissive reuse phrases.

London, Edinburgh, Cardiff, Glasgow, Birmingham & Manchester

- Supply: Workplace for Nationwide Statistics (ONS) — Counties and Unitary Authorities (Could 2023), UK BGC and Areas (December 2023) EN BGC.

- License: Open Authorities Licence v3.0 (OGL).

- Phrases: You might be free to make use of, modify, and share the information (even commercially) so long as you present attribution.

UK Define

- Supply: Pure Earth — Admin 0 — Nations.

- License: Public Area (No restrictions).Quotation:

- Pure Earth. Admin 0 — Nations. Public area. Obtainable from: https://www.naturalearthdata.com

Metropolis boundary code

Right here is the Python code you should utilize to obtain the information recordsdata for every metropolis and confirm the boundaries on a map.

Earlier than working the principle code, please guarantee you’ve put in the next libraries. You should use pip or one other technique of your selection for this.

geopandas

matplotlib

requests

pandas

duckdb

jupyterimport requests, json

import geopandas as gpd

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# ---------- ONS endpoints ----------

LAD24_FS = "https://services1.arcgis.com/ESMARspQHYMw9BZ9/arcgis/relaxation/companies/Local_Authority_Districts_May_2024_Boundaries_UK_BGC/FeatureServer/0/question"

REGION23_FS = "https://services1.arcgis.com/ESMARspQHYMw9BZ9/arcgis/relaxation/companies/Regions_December_2023_Boundaries_EN_BGC/FeatureServer/0/question"

BUA_FS = "https://services1.arcgis.com/ESMARspQHYMw9BZ9/arcgis/relaxation/companies/BUA_2022_GB/FeatureServer/0/question"

# ---------- Helpers ----------

def arcgis_geojson(url, params):

r = requests.get(url, params={**params, "f": "geojson"}, timeout=90)

r.raise_for_status()

return r.json()

def sql_quote(s: str) -> str:

return "'" + s.exchange("'", "''") + "'"

def fetch_lads_by_names(names):

the place = "LAD24NM IN ({})".format(",".be part of(sql_quote(n) for n in names))

knowledge = arcgis_geojson(LAD24_FS, {

"the place": the place,

"outFields": "LAD24NM",

"returnGeometry": "true",

"outSR": "4326"

})

gdf = gpd.GeoDataFrame.from_features(knowledge.get("options", []), crs="EPSG:4326")

if gdf.empty:

increase RuntimeError(f"No LADs discovered for: {names}")

return gdf

def fetch_lad_by_name(title):

return fetch_lads_by_names([name])

def fetch_region_by_name(title):

knowledge = arcgis_geojson(REGION23_FS, {

"the place": f"RGN23NM={sql_quote(title)}",

"outFields": "RGN23NM",

"returnGeometry": "true",

"outSR": "4326"

})

gdf = gpd.GeoDataFrame.from_features(knowledge.get("options", []), crs="EPSG:4326")

if gdf.empty:

increase RuntimeError(f"No Area function for: {title}")

return gdf

def fetch_buas_intersecting_bbox(minx, miny, maxx, maxy):

knowledge = arcgis_geojson(BUA_FS, {

"the place": "1=1",

"geometryType": "esriGeometryEnvelope",

"geometry": json.dumps({

"xmin": float(minx), "ymin": float(miny),

"xmax": float(maxx), "ymax": float(maxy),

"spatialReference": {"wkid": 4326}

}),

"inSR": "4326",

"spatialRel": "esriSpatialRelIntersects",

"outFields": "BUA22NM,BUA22CD,Shape__Area",

"returnGeometry": "true",

"outSR": "4326"

})

return gpd.GeoDataFrame.from_features(knowledge.get("options", []), crs="EPSG:4326")

def aggregate_bua_by_mask(mask_gdf: gpd.GeoDataFrame, label: str) -> gpd.GeoDataFrame:

"""

Fetch BUA 2022 polygons intersecting a masks (LAD/Area union) and dissolve to 1 polygon.

Makes use of Shapely 2.x union_all() to construct the masks geometry.

"""

# Union the masks polygon(s)

mask_union = mask_gdf.geometry.union_all()

# Fetch candidate BUAs through masks bbox, then filter by actual intersection with the union

minx, miny, maxx, maxy = gpd.GeoSeries([mask_union], crs="EPSG:4326").total_bounds

buas = fetch_buas_intersecting_bbox(minx, miny, maxx, maxy)

if buas.empty:

increase RuntimeError(f"No BUAs intersecting bbox for {label}")

buas = buas[buas.intersects(mask_union)]

if buas.empty:

increase RuntimeError(f"No BUAs truly intersect masks for {label}")

dissolved = buas[["geometry"]].dissolve().reset_index(drop=True)

dissolved["city"] = label

return dissolved[["city", "geometry"]]

# ---------- Group definitions ----------

GM_10 = ["Manchester","Salford","Trafford","Stockport","Tameside",

"Oldham","Rochdale","Bury","Bolton","Wigan"]

WMCA_7 = ["Birmingham","Coventry","Dudley","Sandwell","Solihull","Walsall","Wolverhampton"]

GLASGOW_CR_8 = ["Glasgow City","East Dunbartonshire","West Dunbartonshire",

"East Renfrewshire","Renfrewshire","Inverclyde",

"North Lanarkshire","South Lanarkshire"]

EDINBURGH = "Metropolis of Edinburgh"

CARDIFF = "Cardiff"

# ---------- Construct masks ----------

london_region = fetch_region_by_name("London") # Area masks for London

gm_lads = fetch_lads_by_names(GM_10) # Larger Manchester (10)

wmca_lads = fetch_lads_by_names(WMCA_7) # West Midlands (7)

gcr_lads = fetch_lads_by_names(GLASGOW_CR_8) # Glasgow Metropolis Area (8)

edi_lad = fetch_lad_by_name(EDINBURGH) # Single LAD

cdf_lad = fetch_lad_by_name(CARDIFF) # Single LAD

# ---------- Combination BUAs by every masks ----------

layers = []

london_bua = aggregate_bua_by_mask(london_region, "London (BUA 2022 mixture)")

london_bua.to_file("london_bua_aggregate.geojson", driver="GeoJSON")

layers.append(london_bua)

man_bua = aggregate_bua_by_mask(gm_lads, "Manchester (BUA 2022 mixture)")

man_bua.to_file("manchester_bua_aggregate.geojson", driver="GeoJSON")

layers.append(man_bua)

bham_bua = aggregate_bua_by_mask(wmca_lads, "Birmingham (BUA 2022 mixture)")

bham_bua.to_file("birmingham_bua_aggregate.geojson", driver="GeoJSON")

layers.append(bham_bua)

glas_bua = aggregate_bua_by_mask(gcr_lads, "Glasgow (BUA 2022 mixture)")

glas_bua.to_file("glasgow_bua_aggregate.geojson", driver="GeoJSON")

layers.append(glas_bua)

edi_bua = aggregate_bua_by_mask(edi_lad, "Edinburgh (BUA 2022 mixture)")

edi_bua.to_file("edinburgh_bua_aggregate.geojson", driver="GeoJSON")

layers.append(edi_bua)

cdf_bua = aggregate_bua_by_mask(cdf_lad, "Cardiff (BUA 2022 mixture)")

cdf_bua.to_file("cardiff_bua_aggregate.geojson", driver="GeoJSON")

layers.append(cdf_bua)

# ---------- Mix & report areas ----------

cities = gpd.GeoDataFrame(pd.concat(layers, ignore_index=True), crs="EPSG:4326")

# ---------- Plot UK define + the six aggregates ----------

# UK define (Pure Earth 1:10m, easy international locations)

ne_url = "https://uncooked.githubusercontent.com/nvkelso/natural-earth-vector/grasp/geojson/ne_10m_admin_0_countries.geojson"

world = gpd.read_file(ne_url)

uk = world[world["ADMIN"] == "United Kingdom"].to_crs(4326)

# Crop body to our cities

minx, miny, maxx, maxy = cities.total_bounds

uk_crop = uk.cx[minx-5 : maxx+5, miny-5 : maxy+5]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(9, 10), dpi=150)

uk_crop.boundary.plot(ax=ax, coloration="black", linewidth=1.2)

cities.plot(ax=ax, column="metropolis", alpha=0.45, edgecolor="black", linewidth=0.8, legend=True)

# Label every polygon utilizing an inside level

label_pts = cities.representative_point()

for (x, y), title in zip(label_pts.geometry.apply(lambda p: (p.x, p.y)), cities["city"]):

ax.textual content(x, y, title, fontsize=8, ha="heart", va="heart")

ax.set_title("BUA 2022 Aggregates: London, Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Cardiff", fontsize=12)

ax.set_xlim(minx-1, maxx+1)

ax.set_ylim(miny-1, maxy+1)

ax.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="field")

ax.set_xlabel("Longitude"); ax.set_ylabel("Latitude")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.present()After working this code, it’s best to have 6 GeoJSON recordsdata saved in your present listing, and also you must also see an output like this, which visually tells us that our metropolis boundary recordsdata comprise legitimate knowledge.

Getting our accident knowledge

Our remaining piece of the information puzzle is the accident knowledge. The UK authorities publishes stories on car accident knowledge overlaying five-year durations. The most recent knowledge covers the interval from 2019 to 2024. This knowledge set covers the complete UK, so we might want to course of it to extract solely the information for the six cities we’re thinking about. That’s the place DuckDB will are available, however extra on that later.

To view or obtain the accident knowledge in CSV format (Supply: Division for Transport — Street Security Knowledge), click on the hyperlink under

As with town boundary knowledge, that is additionally revealed underneath the Open Authorities Licence v3.0 (OGL 3.0) and as such has the identical licence circumstances.

The accident knowledge set incorporates a lot of fields, however for our functions, we’re solely thinking about 3 of them:

latitude

longitude

number_of_casualtiesTo acquire our casualty counts for every metropolis is now only a 3-step course of.

1/ Loading the accident knowledge set into DuckDB

In case you’ve by no means encountered DuckDB earlier than, the TL;DR is that it’s a super-fast, in-memory (may also be persistent) database written in C++ designed for analytical SQL workloads.

One of many major causes I like it’s its pace. It’s one of many quickest third-party knowledge analytics libraries I’ve used. It is usually very extensible via using extensions such because the geospatial one, which we’ll use now.

Now we are able to load the accident knowledge like this.

import requests

import duckdb

# Distant CSV (final 5 years collisions)

url = "https://knowledge.dft.gov.uk/road-accidents-safety-data/dft-road-casualty-statistics-collision-last-5-years.csv"

local_file = "collisions_5yr.csv"

# Obtain the file

r = requests.get(url, stream=True)

r.raise_for_status()

with open(local_file, "wb") as f:

for chunk in r.iter_content(chunk_size=8192):

f.write(chunk)

print(f"Downloaded {local_file}")

# Join as soon as

con = duckdb.join(database=':reminiscence:')

# Set up + load spatial on THIS connection

con.execute("INSTALL spatial;")

con.execute("LOAD spatial;")

# Create accidents desk with geometry

con.execute("""

CREATE TABLE accidents AS

SELECT

TRY_CAST(Latitude AS DOUBLE) AS latitude,

TRY_CAST(Longitude AS DOUBLE) AS longitude,

TRY_CAST(Number_of_Casualties AS INTEGER) AS number_of_casualties,

ST_Point(TRY_CAST(Longitude AS DOUBLE), TRY_CAST(Latitude AS DOUBLE)) AS geom

FROM read_csv_auto('collisions_5yr.csv', header=True, nullstr='NULL')

WHERE

TRY_CAST(Latitude AS DOUBLE) IS NOT NULL AND

TRY_CAST(Longitude AS DOUBLE) IS NOT NULL AND

TRY_CAST(Number_of_Casualties AS INTEGER) IS NOT NULL

""")

# Fast preview

print(con.execute("DESCRIBE accidents").df())

print(con.execute("SELECT * FROM accidents LIMIT 5").df())You need to see the next output.

Downloaded collisions_5yr.csv

column_name column_type null key default additional

0 latitude DOUBLE YES None None None

1 longitude DOUBLE YES None None None

2 number_of_casualties INTEGER YES None None None

3 geom GEOMETRY YES None None None

latitude longitude number_of_casualties

0 51.508057 -0.153842 3

1 51.436208 -0.127949 1

2 51.526795 -0.124193 1

3 51.546387 -0.191044 1

4 51.541121 -0.200064 2

geom

0 [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, ...

1 [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, ...

2 [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, ...

3 [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, ...

4 [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, ...2/ Loading the city boundary data using DuckDB spatial functions

The function we’ll be using to do this is called ST_READ, which can read and import a variety of geospatial file formats using the GDAL library.

city_files = {

"London": "london_bua_aggregate.geojson",

"Edinburgh": "edinburgh_bua_aggregate.geojson",

"Cardiff": "cardiff_bua_aggregate.geojson",

"Glasgow": "glasgow_bua_aggregate.geojson",

"Manchester": "manchester_bua_aggregate.geojson",

"Birmingham": "birmingham_bua_aggregate.geojson"

}

for city, file in city_files.items():

con.execute(f"""

CREATE TABLE {city.lower()} AS

SELECT

'{city}' AS city,

geom

FROM ST_Read('{file}')

""")

con.execute("""

CREATE TABLE cities AS

SELECT * FROM london

UNION ALL SELECT * FROM edinburgh

UNION ALL SELECT * FROM cardiff

UNION ALL SELECT * FROM glasgow

UNION ALL SELECT * FROM manchester

UNION ALL SELECT * FROM birmingham

""")3/ The next step is to join accidents to the city polygons and count casualties.

The key geospatial function we use this time is called ST_WITHIN. It returns TRUE if the first geometry point is within the boundary of the second.

import duckdb

casualties_per_city = con.execute("""

SELECT

c.city,

SUM(a.number_of_casualties) AS total_casualties,

COUNT(*) AS accident_count

FROM accidents a

JOIN cities c

ON ST_Within(a.geom, c.geom)

GROUP BY c.city

ORDER BY total_casualties DESC

""").df()

print("Casualties per city:")

print(casualties_per_city)Note that I ran the above query on a powerful desktop, and it still took a few minutes to return results, so please be patient. However, eventually, you should see an output similar to this.

Casualties per city:

city total_casualties accident_count

0 London 134328.0 115697

1 Birmingham 14946.0 11119

2 Manchester 4518.0 3502

3 Glasgow 3978.0 3136

4 Edinburgh 3116.0 2600

5 Cardiff 1903.0 1523Analysis

It’s no surprise that London has, overall, the most significant number of casualties. But for its size, is it more or less dangerous to drive or be a pedestrian in than in the other cities?

There is clearly an issue with the casualty figures for Manchester and Glasgow. They should both be larger, based on their city sizes. The suggestion is that this could be because many of the busy ring roads and metro fringe roads (M8/M74/M77; M60/M62/M56/M61) associated with each city are sitting just outside their tight BUA polygons, leading to a significant under-representation of accident and casualty data. I’ll leave that investigation as an exercise for the reader!

For our final determination of driver safety, we need to know each city’s area size so we can calculate the casualty rate per km².

Luckily, DuckDB has a function for that. ST_AREA computes the area of a geometry.

# --- Compute areas in km² (CRS84 -> OSGB 27700) ---

print("nCalculating areas in km^2...")

areas = con.execute("""

SELECT

city,

ST_Area(

ST_MakeValid(

ST_Transform(

-- ST_Simplify(geom, 0.001), -- Experiment with epsilon value (e.g., 0.001 degrees)

geom,

'OGC:CRS84','EPSG:27700'

)

)

) / 1e6 AS area_km2

FROM cities

ORDER BY area_km2 DESC;

""").df()

print("City Areas:")

print(areas.round(2))I obtained this output, which appears to be about right.

city area_km2

0 London 1321.45

1 Birmingham 677.06

2 Manchester 640.54

3 Glasgow 481.49

4 Edinburgh 123.00

5 Cardiff 96.08We now have all the data we need to declare which city has the safest drivers in the UK. Remember, the lower the “safety_index” number, the safer.

city area_km2 casualties safety_index (casualties/area)

0 London 1321.45 134328 101.65

1 Birmingham 677.06 14946 22.07

2 Manchester 640.54 4518 7.05

3 Glasgow 481.49 3978 8.26

4 Edinburgh 123.00 3116 25.33

5 Cardiff 96.08 1903 19.08I’m not comfortable including the results for both Manchester and Glasgow due to the doubts on their casualty counts that we mentioned before.

Taking that into account, and because I’m the boss of this article, I’m declaring Cardiff as the winner of the prize for the safest city from a driver and pedestrian perspective. What do you think of these results? Do you live in one of the cities I looked at? If so, do the results support your experience of driving or being a pedestrian there?

Summary

We examined the feasibility of performing exploratory data analysis on a geospatial dataset. Our goal was to determine which of the UK’s six leading cities were safest to drive in or be a pedestrian in. Using a combination of GeoPandas and DuckDB, we were able to:

- Use Geopandas to download city boundary data from an official government website that reasonably accurately represents the size of each city.

- Download and post-process an extensive 5-year accident survey CSV to obtain the three fields of interest it contained, namely latitude, longitude and number of road accident casualties.

- Join the accident data to the city boundary data on latitude/longitude using DuckDB geospatial functions to obtain the total number of casualties for each city over 5 years.

- Used DuckDB geospatial functions to calculate the size in km² of each city.

- Calculated a safety index for each city, being the number of casualties in each city divided by its size. We disregarded two of our results due to doubts about the accuracy of some of the data. We calculated that Cardiff had the lowest safety index score and was, therefore, deemed the safest of the cities we surveyed.

Given the right input data, geospatial analysis using the tools I describe could be an invaluable aid across many industries. Think of traffic and accident analysis (as I’ve shown), flood, deforestation, forest fire and drought analysis come to mind too. Basically, any system or process that is connected to a spatial coordinate system is ripe for exploratory data analysis by anyone.